The classical music composers of the 19th century

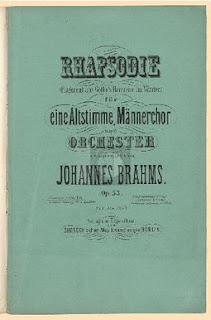

Johannes

Brahms

«Music has healing power. It has the ability to get people out of themselves for a few hours. “Elton John.

German

composer

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

Karl Geiringer

The

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 • Article

History

Written by

Robert Simpson,

Why is Johannes Brahms important?

Johannes

Brahms was a German composer and pianist of the Romantic period, but he was

more a disciple of the Classical tradition. He wrote in many genres, including

symphonies, concerti, chamber music, piano works, and choral compositions, many

of which reveal the influence of folk music.

What is Johannes Brahms famous for?

Throughout

Johannes Brahms’s career there is a variety of expression—from the subtly

humorous to the tragic—but his larger works show an increasing mastery of

movement and an ever-greater economy and concentration. Some of his best-known

compositions included Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Wiegenlied, Op. 49, No. 4, and

Hungarian Dances.

What was Johannes Brahms’s family like?

Johannes

Brahms was the son of Jakob Brahms, an impecunious horn and double bass player,

who was Johannes’s first teacher. Johannes never married, but he had a close

relationship with the pianist Clara Schumann, who was married to his champion,

composer Robert Schumann.

How did Johannes Brahms become famous?

The

violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim, whom Johannes Brahms befriended in 1853, instantly

realized Brahms’s talent and recommended him to the composer Robert Schumann.

Schumann praised Brahms’s compositions in the periodical Neue Zeitschrift für

Musik. The article created a sensation. From this moment Brahms was a force in

the world of music.

How did Johannes Brahms died?

In

1896, Johannes Brahms was compelled to seek medical treatment, in the course of

which his liver was discovered to be seriously diseased. He appeared for the

last time at a concert in March 1897, and in Vienna, in April 1897, he died of

cancer.

Aparment Hamburg

Johannes Brahms, (born May 7, 1833, Hamburg [Germany]—died April 3, 1897, Vienna,

Austria-Hungary [now in Austria]), German composer and pianist of the Romantic

period, who wrote symphonies, concerti, chamber music, piano works, choral

compositions, and more than 200 songs. Brahms was the great master of symphonic

and sonata style in the second half of the 19th century. He can be viewed as

the protagonist of the Classical tradition of Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven in a period when the standards of this

tradition were being questioned or overturned by the Romantics.

The

young pianist and music director

The

son of Jakob Brahms, an impecunious horn and double bass player, Johannes

showed early promise as a pianist. He first studied music with his father and,

at age seven, was sent for piano lessons to F.W. Cossel, who three years later

passed him to his own teacher, Eduard Marxsen. Between ages 14 and 16 Brahms

earned money to help his family by playing in rough inns in the dock area of

Hamburg and meanwhile composing and sometimes giving recitals. In 1850 he met

Eduard Reményi, a Jewish Hungarian violinist, with whom he gave concerts and

from whom he learned something of Roma music—an influence that remained with

him always.

Johannes

Brahms

The

first turning point came in 1853, when he met the violin virtuoso Joseph

Joachim, who instantly realized the talent of Brahms. Joachim in turn

recommended Brahms to the composer Robert Schumann, and an immediate friendship

between the two composers resulted. Schumann wrote enthusiastically about

Brahms in the periodical Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, praising his compositions.

The article created a sensation. From this moment Brahms was a force in the

world of music, though there were always factors that made difficulties for

him.

Robert Shuman

The

chief of these was the nature of Schumann’s panegyric itself. There was already

conflict between the “neo-German” school, dominated by Franz Liszt and Richard

Wagner, and the more conservative elements, whose main spokesman was Schumann.

The latter’s praise of Brahms displeased the former, and Brahms himself, though

kindly received by Liszt, did not conceal his lack of sympathy with the

self-conscious modernists. He was therefore drawn into controversy, and most of

the disturbances in his otherwise uneventful personal life arose from this

situation. Gradually Brahms came to be on close terms with the Schumann

household, and, when Schumann was first taken mentally ill in 1854, Brahms

assisted Clara Schumann in managing her family. He appears to have fallen in

love with her; but, though they remained deep friends after Schumann’s death in

1856, their relationship did not, it seems, go further.

The nearest Brahms ever came to marriage was in his affair with Agathe von Siebold in 1858; from this he recoiled suddenly, and he was never thereafter seriously involved in the prospect.

Clara Shuman

The reasons for this are unclear, but probably his

immense reserve and his inability to express emotions in any other way but

musically were responsible, and he no doubt was aware that his natural

irascibility and resentment of sympathy would have made him an impossible

husband. He wrote in a letter, “I couldn’t bear to have in the house a woman

who has the right to be kind to me, to comfort me when things go wrong.” All

this, together with his intense love of children and animals, goes some way to

explain certain aspects of his music, its concentrated inner reserve that hides

and sometimes dams powerful currents of feeling.

Between

1857 and 1860 Brahms moved between the court of Detmold—where he taught the

piano and conducted a choral society—and Göttingen, while in 1859 he was

appointed conductor of a women’s choir in Hamburg. Such posts provided valuable

practical experience and left him enough time for his own work. At this point

Brahms’s productivity increased, and, apart from the two delightful Serenades

for orchestra and the colourful first String Sextet in B-flat Major (1858–60),

he also completed his turbulent Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor (1854–58).

By

1861 he was back in Hamburg, and in the following year he made his first visit

to Vienna, with some success. Having failed to secure the post of conductor of

the Hamburg Philharmonic concerts, he settled in Vienna in 1863, assuming

direction of the Singakademie, a fine choral society. His life there was on the

whole regular and quiet, disturbed only by the ups and downs of his musical

success, by altercations occasioned by his own quick temper and by the often

virulent rivalry between his supporters and those of Wagner and Anton Bruckner,

and by one or two inconclusive love affairs. His music, despite a few failures

and constant attacks by the Wagnerites, was established, and his reputation

grew steadily. By 1872 he was principal conductor of the Society of Friends of

Music (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde), and for three seasons he directed the

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. His choice of music was not as conservative as

might have been expected, and though the “Brahmins” continued their war against

Wagner, Brahms himself always spoke of his rival with respect. Brahms is

sometimes portrayed as unsympathetic toward his contemporaries. His kindness to

Antonín Dvořák is always acknowledged, but his encouragement even of such a

composer as the young Gustav Mahler is not always realized, and his enthusiasm

for Carl Nielsen’s First Symphony is not generally known.

In

between these two appointments in Vienna, Brahms’s work flourished and some of

his most significant works were composed. The year 1868 witnessed the completion

of his most famous choral work, Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), which

had occupied him since Schumann’s death. This work, based on biblical texts

selected by the composer, made a strong impact at its first performance at

Bremen on Good Friday, 1868; after this, it was performed throughout Germany.

With the Requiem, which is still considered one of the most significant works

of 19th-century choral music, Brahms moved into the front rank of German

composers.

Brahms

was also writing successful works in a lighter vein. In 1869 he offered two

volumes of Hungarian Dances for piano duet; these were brilliant arrangements

of Roma tunes he had collected in the course of the years. Their success was

phenomenal, and they were played all over the world. In 1868–69 he composed his

Liebeslieder (Love Songs) waltzes, for vocal quartet and four-hand piano

accompaniment—a work sparkling with humour and incorporating graceful Viennese

dance tunes. Some of his greatest songs were also written at this time.

Maturity

and fame of Johannes Brahms

Johannes

Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major

By

the 1870s Brahms was writing significant chamber works and was moving with

great deliberation along the path to purely orchestral composition. In 1873 he

offered the masterly orchestral version of his Variations on a Theme by Haydn.

After this experiment, which even the self-critical Brahms had to consider

completely successful, he felt ready to embark on the completion of his

Symphony No. 1 in C Minor. This magnificent work was completed in 1876 and

first heard in the same year. Now that the composer had proved to himself his

full command of the symphonic idiom, within the next year he produced his

Symphony No. 2 in D Major (1877). This is a serene and idyllic work, avoiding

the heroic pathos of Symphony No. 1. He let six years elapse before his

Symphony No. 3 in F Major (1883). In its first three movements this work too

appears to be a comparatively calm and serene composition—until the finale,

which presents a gigantic conflict of elemental forces. Again after only one

year, Brahms’s last symphony, No. 4 in E Minor (1884–85), was begun. This work

may well have been inspired by the ancient Greek tragedies of Sophocles that

Brahms had been reading at the time. The symphony’s most important movement is

once more the finale. Brahms took a simple theme he found in J.S. Bach’s

Cantata No. 150 and developed it in a set of 30 highly intricate variations,

but the technical skill displayed here is as nothing compared with the clarity

of thought and the intensity of feeling.

Gradually

Brahms’s renown spread beyond Germany and Austria. Switzerland and the

Netherlands showed true appreciation of his art, and Brahms’s concert tours to

these countries as well as to Hungary and Poland won great acclaim. The

University of Breslau (now the University of Wrocław, Poland) conferred an

honorary degree on him in 1879. The composer thanked the university by writing

the Academic Festival Overture (1881) based on various German student songs. Among

his other orchestral works at this time were the Violin Concerto in D Major

(1878) and the Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major (1881).

By

now Brahms’s contemporaries were keenly aware of the outstanding significance

of his works, and people spoke of the “three great Bs” (meaning Bach,

Beethoven, and Brahms), to whom they accorded the same rank of eminence. Yet

there was a sizable circle of musicians who did not admit Brahms’s greatness.

Fervent admirers of the avant-garde composers of the day, most notably Liszt

and Wagner, looked down on Brahms’s contributions as too old-fashioned and

inexpressive.

Brahms

remained in Vienna for the rest of his life. He resigned as director of the

Society of Friends of Music in 1875, and from then on devoted his life almost

solely to composition. When he went on concert tours, he conducted or performed

(on the piano) only his own works. He maintained a few close personal

friendships and remained a lifelong bachelor. He spent his summers traveling in

Italy, Switzerland, and Austria. During these years Brahms composed the boldly

conceived Double Concerto in A Minor (1887) for violin and cello, the powerful

Piano Trio No. 3 in C Minor (1886), and the Violin Sonata in D Minor (1886–88).

He also completed the radiantly joyous first String Quintet in F Major (1882)

and the energetic second String Quintet in G Major (1890).

Final

years

In 1891 Brahms was inspired to write

chamber music for the clarinet owing to his acquaintance with an outstanding

clarinetist, Richard Mühlfeld, whom he had heard perform some months before.

With Mühlfeld in mind, Brahms wrote his Trio for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano

(1891); the great Quintet for Clarinet and Strings (1891); and two Sonatas for

Clarinet and Piano (1894). These works are perfect in structure and beautifully

adapted to the potentialities of the wind instrument.

In 1896 Brahms completed his Vier ernste

Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), for bass voice and piano, on texts from both the

Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, a pessimistic work dealing with the vanity

of all earthly things and welcoming death as the healer of pain and weariness.

The conception of this work arose from Brahms’s thoughts of Clara Schumann,

whose physical condition had gravely deteriorated. On May 20, 1896, Clara died,

and soon afterward Brahms himself was compelled to seek medical treatment, in

the course of which his liver was discovered to be seriously diseased. He

appeared for the last time at a concert in March 1897, and in Vienna, in April

1897, he died of cancer.

Aims and achievements of Johannes Brahms

Brahms’s music complemented and counteracted the rapid growth of Romantic individualism in the second half of the 19th century. He was a traditionalist in the sense that he greatly revered the subtlety and power of movement displayed by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, with an added influence from Franz Schubert.

The Romantic composers’ preoccupation

with the emotional moment had created new harmonic vistas, but it had two

inescapable consequences. First, it had produced a tendency toward rhapsody

that often resulted in a lack of structure. Second, it had slowed down the

processes of music, so that Wagner had been able to discover a means of writing

music that moved as slowly as his often-argumentative stage action. Many

composers were thus decreasingly concerned to preserve the skill of taut,

brilliant, and dramatic symphonic development that had so eminently

distinguished the masters at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries,

culminating in Beethoven’s chamber music and symphonies.

Strauss and Brahms

Brahms was acutely conscious of this loss,

repudiated it, and set himself to compensate for it in order to keep alive a

force he felt strongly was far from spent. But Brahms was desirous not of

reproducing old styles but of infusing the language of his own time with

constructive power. Thus his musical language actually bears little resemblance

to Beethoven’s or even Schubert’s; harmonically it was much influenced by

Schumann and even to some extent by Wagner. It is Brahms’s supple and masterful

control of rhythm and movement that distinguishes him from all his

contemporaries. It is often supposed that his sense of movement was slower than

that of his most admired predecessor, Beethoven, but Brahms was always able to

vary the pace of his musical thought in a startling manner, often tightening

and speeding it without a change of tempo. It is a question of subtlety in command

of tonality, harmony, and rhythm, and no 19th-century composer after Beethoven

is able to surpass him in this respect. At all periods in Brahms’s work one

finds a great variety of expression—from the subtly humorous to the tragic—but

his larger works show an increasing mastery of movement and an ever-greater

economy and concentration. Ultimately, Brahms’s power of movement stems partly

from a source that may seem paradoxical. He was the most deeply versed of

Classical composers in the music of the distant past, and he took the lessons

he learned from the polyphonic school of the 16th century and applied them to

the forms and the instrumental and vocal resources of his own time. Thus it was

by way of a new approach to texture, drawn from very old models, that he

revitalized a 19th-century rhythmic language that had been in danger of

expiring from textural and harmonic stagnation.

In his orchestral works Brahms displays an

unmistakable and highly distinctive deployment of tone colour, especially in

his use of woodwind and brass instruments and in his string writing, but the

important thing about it is that colour is deployed, rather than laid on for

its own sake. A close relationship between orchestration and architecture

dominates these works, with the orchestration contributing as much to the tonal

colouring as do the harmonies and tonalities and the changing nature of the

themes. As in the concerti of Mozart and Beethoven, such an attitude to

orchestration proves in Brahms to be peculiarly adapted to the more subtle

aspects of the relation between orchestra and soloist. The Classical concerto

had achieved in Mozart’s mature works for piano and orchestra an unsurpassable

degree of organization, and Beethoven had further extended the genre’s scale of

design and range of expression. The higher subtleties of such works inevitably

escaped many subsequent composers; Felix Mendelssohn had “abolished” the

opening orchestral tutti, or ritornello, and had been followed in this regard

by many other lesser composers. Brahms saw that this was essentially

debilitating and set himself to recover the depth and grandeur of the concerto

idea. Like Mozart and Beethoven, he realized that the long introductory passage

of the orchestra, far from being superfluous, was the means of sharpening and

deepening the complex relationship of orchestra to solo, especially when the

time came for recapitulation, where an entirely new and often revelatory

distribution of themes, keys, instrumentation, and tensions was possible. Many

of Brahms’s contemporaries thought him reactionary on this account, but the

result is that Brahms’s concerti have withstood wear and tear far better than

many works thought in their day to outshine them.

At the other end of the scale, Brahms was a

masterly miniaturist, not only in many of his fine and varied songs but also in

his terse, cunningly wrought, intensely personal late piano works. As a song

composer, he ranged from the complex and highly organized to the extremely

simple, strophic type; his melodic invention is always original and direct,

while the accompaniments are deeply evocative without ever being merely

picturesque. The late piano music, usually of small dimension but wide

implication, is generally expressive of a profound isolation of mind and heart

and is therefore not readily approachable, while its apparent overall tone and

mood may seem to the superficial ear monotonous. But each individual piece has

a quiet and intense quality of its own that renders the occasional outburst of

angry passion the more potent; the internal economy and subtlety of these works

is extraordinary.

Viena

With affection,

Ruben

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment