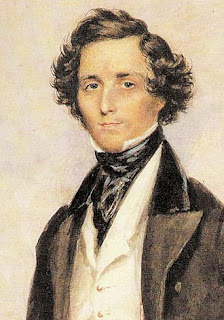

Felix Mendelssohn

German musician and compose

Source:

Britannica

painting by

Wilhelm Hensel.

Felix Mendelssohn

German musician

and composer

Also known as:

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

Written by

Quick Facts

In full: Jakob Ludwig Felix

Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

Born: February 3, 1809, Hamburg

[Germany]

Died: November 4, 1847, Leipzig (aged

38)

Notable Works: “A Midsummer Night’s

Dream” “Briefe über die Empfindungen” “Elijah, Op. 70” “Hymn of Praise”

“Italian Symphony” “Octet for Strings in E-Flat Major, Op. 20” “Scottish

Symphony” “Songs Without Words” “St. Paul” “String Octet in E Flat Major” “The

Hebrides, Op. 26” “Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64”

Movement / Style: Romanticism

Signature

Felix Mendelssohn (born February 3,

1809, Hamburg [Germany]—died November 4, 1847, Leipzig) was a German composer,

pianist, musical conductor, and teacher, one of the most-celebrated figures of

the early Romantic period. In his music, Mendelssohn largely observed Classical

models and practices while initiating key aspects of Romanticism—the artistic

movement that exalted feeling and the imagination above rigid forms and

traditions. Among his most famous works are Overture to A Midsummer Night’s

Dream (1826), Italian Symphony (1833), a violin concerto (1844), two piano

concerti (1831, 1837), the oratorio Elijah (1846), and several pieces of

chamber music. He was a grandson of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn.

Early

life and works

1821

Felix was

born of Jewish parents, Abraham and Lea Salomon Mendelssohn, from whom he took

his first piano lessons. Though the Mendelssohn family was proud of their

ancestry, they considered it desirable in accordance with 19th-century liberal

ideas to mark their emancipation from the ghetto by adopting the Christian

faith. Accordingly, Felix, together with his brother and two sisters, was

baptized in 1816 as a Lutheran. In 1822, when his parents were also baptized,

the entire family adopted the surname Bartholdy, following the example of

Felix’s maternal uncle, who had chosen to adopt the name of a family farm.

In 1811,

during the French occupation of Hamburg, the family had moved to Berlin, where

Mendelssohn studied the piano with Ludwig Berger and composition with Carl

Friedrich Zelter, who, as a composer and teacher, exerted an enormous influence

on his development. Other teachers gave the Mendelssohn children lessons in

literature and landscape painting, with the result that at an early age

Mendelssohn’s mind was widely cultivated. His personality was nourished by a

broad knowledge of the arts and was also stimulated by learning and

scholarship. He traveled with his sister to Paris, where he took further piano

lessons and where he appears to have become acquainted with the music of

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mendelssohn

was an extemely precocious musical composer. He wrote numerous compositions

during his boyhood, among them 5 operas, 11 symphonies for string orchestra,

concerti, sonatas, and fugues. Most of these works were long preserved in

manuscript in the Prussian State Library in Berlin but are believed to have

been lost in World War II. He made his first public appearance in 1818—at age

nine—in Berlin.

In 1821

Mendelssohn was taken to Weimar to meet J.W. von Goethe, for whom he played

works of J.S. Bach and Mozart and to whom he dedicated his Piano Quartet No. 3.

in B Minor (1825). A remarkable friendship developed between the aging poet and

the 12-year-old musician. In Paris in 1825 Luigi Cherubini discerned

Mendelssohn’s outstanding gifts. The next year he reached his full stature as a

composer with the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The atmospheric

effects and the fresh lyrical melodies in this work revealed the mind of an

original composer, while the animated orchestration looked forward to the

orchestral manner of Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov.

Mendelssohn

also became active as a conductor. On March 11, 1829, at the Singakademie,

Berlin, he conducted the first performance since Bach’s death of the St.

Matthew Passion, thus inaugurating the Bach revival of the 19th century.

Meanwhile he had visited Switzerland and had met Carl Maria von Weber, whose

opera Der Freischütz, given in Berlin in 1821, encouraged him to develop a

national character in music. Mendelssohn’s great work of this period was the

String Octet in E Flat Major (1825), displaying not only technical mastery and

an almost unprecedented lightness of touch but great melodic and rhythmic

originality. Mendelssohn developed in this work the genre of the swift-moving

scherzo (a playful musical movement) that he would also use in the incidental

music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1843).

In the

spring of 1829 Mendelssohn made his first journey to England, conducting his

Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (1824) at the London Philharmonic Society. In the

summer he went to Scotland, of which he gave many poetic accounts in his

evocative letters. He went there “with a rake for folksongs, an ear for the

lovely, fragrant countryside, and a heart for the bare legs of the natives.” At

Abbotsford he met Sir Walter Scott. The literary, pictorial, and musical

elements of Mendelssohn’s imagination are often merged. Describing, in a letter

written from the Hebrides, the manner in which the waves break on the Scottish

coast, he noted down, in the form of a musical symbol, the opening bars of The

Hebrides (1830–32). Between 1830 and 1832 he traveled in Germany, Austria,

Italy, and Switzerland and in 1832 returned to London, where he conducted The

Hebrides and where he published the first book of the piano music he called

Lieder ohne Worte (Songs Without Words), completed in Venice in 1830.

Mendelssohn, whose music in its day was held to be remarkable for its charm and

elegance, was gradually becoming the most popular of 19th-century composers in

England. His main reputation was made in England, which, in the course of his

short life, he visited no fewer than 10 times. At the time of these visits, the

character of his music was held to be predominantly Victorian, and indeed he

eventually became the favourite composer of Queen Victoria herself.

Mendelssohn’s

subtly ironic account of his meeting with the queen and the prince consort at

Buckingham Palace in 1843, to both of whom he was affectionately drawn, shows

him also to have been alive to both the pomp and the sham of the royal

establishment. His Symphony No. 3 in A Minor–Major, or Scottish Symphony, as it

is called, was dedicated to Queen Victoria. And he became endeared to the

English musical public in other ways. The fashion for playing the “Wedding

March” from his A Midsummer Night’s Dream at bridal processions originates from

a performance of this piece at the wedding of the Princess Royal after

Mendelssohn’s death, in 1858. In the meantime he had given the first

performances in London of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Emperor and G Major concerti.

He was among the first to play a concerto from memory in public—Mendelssohn’s

memory was prodigious—and he also became known for his organ works. Later the

popularity of his oratorio Elijah, first produced at Birmingham in 1846,

established Mendelssohn as a composer whose influence on English music equaled

that of George Frideric Handel. After his death this influence was sometimes

held to have had a stifling effect. Later generations of English composers,

enamoured of Richard Wagner, Claude Debussy, or Igor Stravinsky, revolted

against the domination of Mendelssohn and condemned the sentimentality of his

lesser works. But there is no doubt that he had, nevertheless, succeeded in

arousing the native musical genius, at first by his performances and later in

the creative sphere, from a dormant state.

In the summer of 1825, the Mendelssohn

family moved into a mansion at 3 Leipzigerstraße on the outskirts of Berlin

(view of the house in 1900).

A number

of new experiences marked the grand tour that Mendelssohn had undertaken after

his first London visit. Lively details of this tour are found in his long

series of letters. On Goethe’s recommendation he had read Laurence Sterne’s

Sentimental Journey, and, inspired by this work, he recorded his impressions

with great verve. In Venice he was enchanted by the paintings of Titian and

Giorgione. The papal singers in Rome, however, were “almost all unmusical,” and

Gregorian music he found unintelligible. In Rome he describes a “haggard”

colony of German artists “with terrific beards.” Later, at Leipzig, where

Hector Berlioz and Mendelssohn exchanged batons, Berlioz offered an enormous

cudgel of lime tree covered with bark, whereas Mendelssohn playfully presented

his brazen contemporary with a delicate light stick of whalebone elegantly

encased in leather. The contrast between these two batons precisely reflects

the violently conflicting characters of the two composers.

In 1833

Mendelssohn was in London again to conduct his Italian Symphony (Symphony No. 4

in A Major–Minor), and in the same year he became music director of Düsseldorf,

where he introduced into the church services the masses of Beethoven and

Cherubini and the cantatas of Bach. At Düsseldorf, too, he began his first

oratorio, St. Paul. In 1835 he became conductor of the celebrated Gewandhaus

Orchestra at Leipzig, where he not only raised the standard of orchestral

playing but made Leipzig the musical capital of Germany. Frédéric Chopin and

Robert Schumann were among his friends at Leipzig, where, at his first concert

with the Gewandhaus Orchestra, he conducted his overture Meeresstille und

glückliche Fahrt (1828–32; Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage).

Marriage

and maturity of Felix Mendelssohn

Cecile Mendelssohn

In

1835

Mendelssohn was overcome by the death of his father, Abraham, whose dearest

wish had been that his son should complete the St. Paul. He accordingly plunged

into this work with renewed determination and the following year conducted it

at Düsseldorf. The same year at Frankfurt he met Cécile Jeanrenaud, the

daughter of a French Protestant clergyman. Though she was 10 years younger than

himself, that is to say, no more than 16, they became engaged and were married

on March 28, 1837. His sister Fanny, the member of his family who remained

closest to him, wrote of her sister-in-law: “She is amiable, childlike, fresh,

bright and even-tempered, and I consider Felix most fortunate for, though

inexpressibly fond of him, she does not spoil him, but when he is capricious,

treats him with an equanimity which will in course of time most probably cure

his fits of irritability altogether.” This was magnanimous praise on the part

of Fanny, to whom Mendelssohn was drawn by musical as well as emotional ties.

Fanny was not only a composer in her own right—she had herself written some of

the Songs Without Words attributed to her brother—but she seems to have

exercised, by her sisterly companionship, a powerful influence on the

development of his inner musical nature.

Felix

Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64An excerpt from Felix

Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64, played here with piano

accompaniment (“piano reduction”).

Works

written over the following years include the Variations sérieuses (1841), for

piano, the Lobgesang (1840; Hymn of Praise), Psalm CXIV, the Piano Concerto No.

2 in D Minor (1837), and chamber works. In 1838 Mendelssohn began the Violin

Concerto in E Minor–Major. Though he normally worked rapidly, throwing off

works with the same facility as one writes a letter, this final expression of

his lyrical genius compelled his arduous attention over the next six years. In

the 20th century the Violin Concerto was still admired for its warmth of melody

and for its vivacity, and it was also the work of Mendelssohn’s that, for

nostalgic listeners, enshrined the elegant musical language of the 19th

century. Nor was its popularity diminished by the later, more turgid, and often

more dramatic violin concerti of Johannes Brahms, Béla Bartók, and Alban Berg.

It is true that many of Mendelssohn’s works are cameos, delightful portraits or

descriptive pieces, held to lack the characteristic Romantic depth. But

occasionally, as in the Violin Concerto and certain of the chamber works, these

predominantly lyrical qualities, so charming, naive, and fresh, themselves end

by conveying a sense of the deeper Romantic wonder.

In 1843

Mendelssohn founded at Leipzig the conservatory of music where, together with

Schumann, he taught composition. Visits to London and Birmingham followed,

entailing an increasing number of engagements. These would hardly have affected

his normal health; he had always lived on this feverish level. But at Frankfurt

in May 1847 he was greatly saddened by the death of Fanny. It is at any rate

likely that for a person of Mendelssohn’s sensibility, living at such

intensity, the death of this close relative, to whom he was so completely

bound, would undermine his whole being. In fact, after the death of his sister,

his energies deserted him, and, following the rupture of a blood vessel, he soon died.

Legacy

Though

the music

of Mendelssohn, stylish and elegant, does not fill the entire musical scene, as

it was inclined to do in Victorian times, it has elements that unite this

versatile 19th-century composer to the principal artistic figures of his time.

In the Midsummer Night’s Dream music, with its hilarious grunting of an ass on

the bassoon and the evocative effect of Oberon’s horn, Mendelssohn becomes a partner

in Shakespeare’s fairyland kingdom. The blurred impressionist effects in The

Hebrides foreshadow the later developments of the painter J.M.W. Turner. Wagner

understood Mendelssohn’s inventive powers as an orchestrator, as is shown in

his own opera The Flying Dutchman, and, later, the French composers of the 20th

century learned much from his grace and perfection of style.

The

appeal of Mendelssohn’s work has not

dwindled in the 21st century. It is true

that Elijah is not so frequently performed as it once was and some of his

fluent piano works are now overshadowed by the more-enduring works of Beethoven

and Schumann. But the great pictorial works of Mendelssohn, the Scottish and

Italian symphonies, repeatedly yield new vistas, and the Songs Without Words

retain their graceful beauty. Mendelssohn was one of the first of the great

19th-century Romantic composers, and in this sense he remains even today a

figure to be rediscovered.

Aquarell Mendelssohn 1847

Edward

LockspeiserThe Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

With

affection,

Ruben

.jpg)