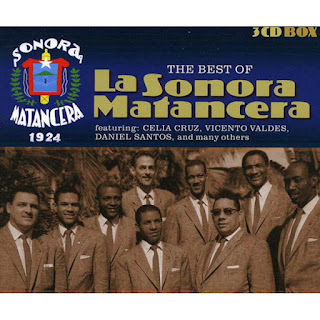

Biography of La Sonora Matancera

The

history, life and musical legacy of La Sonora Matancera

Who is La Sonora Matancera?

La Sonora

Matancera is a group of Cuban and Caribbean popular music.

It was

formed in 1920 in the city of Matanzas, Cuba.

Getting

into Sonora Matancera was a goal for many singers and musicians in training in

the mid-20th century, but the orchestra also grew with those voices and those

performers. In its most splendor stage, there were singers or musicians who

shone with the orchestra, to later develop a successful career as soloists or

with other groups. Among many other

outstanding artists, mention can be made of Celia Cruz, Daniel Santos, Myrta

Silva, Leo Marini, Miguelito Valdés, Bobby Capó, Vicentico Valdés, Alberto

Beltrán, Carlos Argentino, Celio González, Dámaso Pérez Prado, Carmen Delia

Dipiní, Ismael Miranda, Justo Betancourt, Yayo El Indio, Olga Chorens, Toña La

Negra and Víctor Piñero.

Beginnings

of La Sonora Matancera in Music

In 1924,

Valentín Cané had the initiative to create a musical ensemble, forming the

group Tuna Liberal. In that group, the strings predominated, due to the rise of

the son, for which four acoustic guitars were needed. The musicians at that

time were nine Valentín Cané in tres and conducting; Pablo "Bubú"

Vásquez, on double bass, Eugenio Pérez, singer, Manuel Sánchez Jimagua,

timbalito; Ishmael Rules, trumpet; together with the guitarists Domingo Medina,

José Manuel Valera, Julio Gobín and Juan Bautista Llopis.

With the

departure of two members, in 1926 they changed their name to Septeto Soprano,

but soon there was a change to Estudiantina Sonora Matancera. Then they

traveled to Havana, where they contacted the RCA Víctor company, presenting

their first recording in 1928.

In the

thirties, the group began to embrace different rhythms of popular dance music

of the time, with the incorporation of various instruments, such as the grand

piano, which allowed it to expand its range of sounds. In 1935, the name changed definitively to La Sonora

Matancera.

Musical genre of La Sonora Matancera

In her

long musical journey, La Sonora Matancera has interpreted different genres and

variants of Cuban popular music, such as guaracha, son, guajira, bolero and

mambo, among others. According to specialized critics, in its beginnings the

group achieved its own style based on the roots of Cuban music, which became

evident in the way of playing, in the phrasing and in the rhythmic sense of its

singers. This particular way of interpreting their songs was possible, because

the musical arrangements were made especially for the style of each singer.

Over the

years he was incorporating other musical rhythms, until he reached salsa in the

eighties. At that time, some critics say, La Sonora Matancera changed its

style, losing originality. That foray into salsa was mainly due to the entry

into its ranks of musicians trained in New York.

Trajectory

and Legacy of La Sonora Matancera

In 1944,

La Sonora Matancera premiered two songs entitled "Pa' congrí" and

"Coquito caramelado". That same year, he released the single "La

ola marina" and signed a contract with the label Panart Records. During

that decade of the forties they made different presentations in dance

academies, cabarets and the Radio Progreso Cubano station.

In 1946,

La Sonora Matancera experienced its first change in orchestra conduction, its

founder Valentín Cané began to have health problems, which forced him to

gradually move away from his activity in the group. He took over as director

Rogelio Martínez. Before the musical group signed with Panart Records, he

recorded three songs for the Varsity label, which were "Se formed la

rumbantela", "Tumba colorá" and "El cinto de mi

sombrero".

There is

a consensus among those who know the history of La Sonora Matancera, in which

the twelve years that go from 1947 to 1959 were its golden age. In 1947 he

signed with the Stinson record company under the name of Conjunto Tropicavana,

because they had an exclusive contract with the Panart label, that year the

song "A little house is sold". In 1949, they recorded for a short

time with the Cafamo label, later signing for Ansonia Records, a company with

which they presented twenty-two songs, one of them being "Se romó el

muñeco".

In 1950,

they recorded again with RCA Victor, but it was the last time they worked with

that label. After six years they ended, signing with Seeco Records, a company

with which they spent fifteen years, their first song together being

"Knocking on wood". In those years La Sonora Matancera made several

live presentations.

Throughout

the group's musical career, there were many artists who made history inside and

outside of La Sonora Matancera. Celia Cruz, was one of them, she began to sing

in the group at a very young age and her first song was "Cao, cao maní

picao", her interpretations of "Yerbatero moderno" and

"Burundanga" were also successful. She remained in the group until

1965.

In 1951,

La Sonora Matancera premiered the song "Se forma el rumbón", written

by Calixto Leicea. That same year, she also published "Luna

yumurina", a bolero with mambo mixes. The following year, she released the

singles "Choucouné" and "Cuando muere las palabras". In

1953, Daniel Santos left the group, who for a decade and a half increased the

group's international fame.

In 1954,

he left the Bienvenido Granda group, which was also there for almost fifteen

years, his last recording being "Hold your tongue." In 1955, the

group published the song "Si no vuelves" and toured Colombia. They also presented the songs "Una canción",

"Yambú pa' gozar", "El muñeco de la ciudad" and "Las

muchachas".

In 1956,

the singer Celio González entered, who debuted in La Sonora Matancera with the

song "Quémame los ojos". The following year the group made a concert

tour of several countries, such as Peru, Chile and Argentina. That same year

the singer Johnny López recorded the chomba-calypso "Linstead

Market", in August, the Uruguayan Chito Galindo recorded the bolero

"Consuélame".

In 1958,

La Sonora Matancera had the collaboration of the Venezuelan Víctor Piñero, with

a guaracha titled "I don't want anything with his wife". So did

Reynaldo Hierrezuelo, known as Rey Caney, who recorded his first song in

October, the bolero he wrote "Quiero emborracharme." That year,

several members left the musical group, leaving only Celia Cruz as a staff

singer, who performed the last album they recorded in Cuba.

In 1960,

La Sonora Matancera left Cuba and traveled to Mexico, knowing that there would

be no return trip to her country. That year the group premiered the songs

"El Baby", "I'm crazy", in 1961, they published "I

don't know what's wrong with me". In 1962, Víctor Piñero recorded

"Puente sobre el lago", to commemorate the inauguration of the

General Rafael Urdaneta bridge in Maracaibo, Venezuela.

La Sonora

Matancera, ended its contract with Seeco Records in 1966, adopting a new style

for its own label M.R.V.A. At that time, the singers Elliot Romero, Justo

Betancourt, Máximo Barrientos and Tony Díaz joined. From that year, until 1980,

there were several changes in its formation, which blurred part of the musical

identity that characterized it for so many years, but giving way to more modern

sounds, by using electric instruments such as bass and piano. In 1981, he

signed with the Fania Records label, who included him in their new subsidiary

called Bárbaro Records, with which they remained until 1984.

In 1982,

an emotional reunion with Celia Cruz led to the recording of the album

"Feliz encuentro". Two years later, they released the single "El

tornillo", from the album "Tradición". In celebration of the

sixty-five years of La Sonora Matancera, an event was held in Central Park in

New York, United States, on July 1, 1989. They also performed at Carnegie Hall,

the famous concert hall of Manha

members

of La Sonora Matancera

Currently

its members are Valentín Cané, Pablo Vázquez Gobín "Bubú", Rogelio

Martínez Díaz, Ezequiel Frías Gómez "Lino", José Rosario Chávez

"Manteca", Ángel Alfonso Furias "Yiyo" and Carlos Manuel

Díaz Alonso "Caíto".

They passed through the group Bienvenido Granda †,

Pedro Knight †, Calixto Leicea †, Celia Cruz †, Humberto Cané, Daniel Santos †,

Myrta Silva †, Leo Marini †, Miguelito Valdés †, Bobby Capó †, Nelson Pinedo †,

Vicentico Valdés † , Estanislao Sureda "Laíto", Alberto Beltrán †,

Carlos Argentino †, Celio González †, Pérez Prado †, Manuel Sánchez

"Jimagua", Ismael Goberna, Domingo Medina, José Manuel Valera, Juan

Bautista Llopis, Elpidio Vázquez, Carmen Delia Dipiní † , Javier Vázquez, Willy

Rodríguez "El Baby", Alfredo Armenteros "Chocolate"†,

Ismael Miranda, Justo Betancourt, Linda Leída, Gabriel Eladio Peguero, "Yayo

El Indio"†, Welfo Gutiérrez†, Olga Chorens, Gloria Díaz, Tony Álvarez ,

Chito Galindo, Toña la Negra †, Bienvenido León, Elliot Romero, Emilio

Domínguez "El Jarocho", Gladys Julio, Hermanas Lago, Israel del Pino,

Johnny López, Jorge Maldonado, Kary Infante, Manuel Licea "Puntillita"

†, Martha Jean Claude, Máximo Barrientos, Miguel de Gonzalo, Pepe Reyes, Raúl

del Castillo, Reyna Ido Hierrezuelo "Rey Caney", Rodolfo Hoyos, Tony

Díaz, Víctor Piñero†, Vicky Jiménez, Alfredo Valdés, Albertico Pérez.

La Sonora

Matancera has been much more than a group of performers of popular Cuban and

Caribbean rhythms. It is a musical institution, like very few in the world,

that remains active after almost a hundred years. Under the direction of two

exceptional musicians, first its founder Valentín Cané and then Rogelio

Martínez, it was a training center for talented musicians and singers, who in

turn gave brilliance to the orchestra.

Dean of

Cuban ensembles, as Sonora Matancera is also called, it has been one of the

most famous musical groups in America. His music has made several generations

of fans of popular music from the Caribbean dance and enjoy it all over the

world. He had a golden age, where he knew how to interpret music such as

guaguancó, guaracha, jíbara song, merecumbé and cumbia, as well as bolero and

mambo, to make it universal. He adapted to the times and came to be identified

as salsa, another of the great rhythms of Latin Americans. For several decades,

many musical groups emerged following in the footsteps of this unique orchestra

that has known how to make history.

With

affection,

Ruben